Family History from 1862

- OkieState

- Jan 1, 2015

- 16 min read

Updated: Nov 5, 2020

It began with the Homestead Act of 1862, signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States of America. This Act gave any applicant freehold title to up to 160 acres of undeveloped federal land outside the original 13 colonies. The law required three steps: (1) file an application, (2) improve the land, and (3) file for deed of title. Anyone who had never taken up arms against the U.S. Government, including freed slaves, could file an application and evidence of improvements to a federal land office. It is important to note that only about 40% of the applicants who started the process were able to complete it and obtain title to their homestead land. It was not for the faint or weary at heart.

With news of the Homestead Act spreading into other countries, our ancestors, the Czechs, were some of many that began their voyage to America in the 1870's. Ideas of making a better home for their children in a country with less hardships and strife became their passion, though little did they know the hardships before them. They especially sought religious freedom. They also wished to rid themselves from compulsory military training under the rule of Austria. Simply, they wanted to be free.

It took the early Czechs six to eight weeks, enduring rough waters at sea to come to America. They lived those weeks on sailboats, in small, eight-by-ten-foot rooms designed to house a few people, but often housing entire extended families. The living conditions during their journey were often deplorable, but these travelers knew the trip would be well worth the sacrifice, for America and a piece of its land waited their arrival.

Most of the ships landed at Baltimore, Maryland. There, families took stock of their money and talents before setting out across land. The Homestead Act that lured them declared that settlers must improve the land with a dwelling and grow crops. Should these conditions be met after 5 years and with a fee of $18, anyone could be presented a deed free and clear. But this was not a calling for those who were tied to a life of luxury, or for those accustomed to a life of physical and mental pleasures. This was a calling for those willing to take a risk and experience the unknown. Only those driven to work hard for a life of freedom they had never experienced, those who burned with a sense of individualism and a survival-of-the-fittest mentality, were drawn to the cause. The lives and all the possessions they had in their native land would be reduced to the only things that truly mattered to them - their faith, music, dancing, and customary foods, especially kolaches. But as long as they had these things, they knew it would be okay. George and Mary Kassik knew it would be okay. They could feel it deep inside them, driving them to pursue their dreams and to never look back. This is their story.

George (Jiri) Kassik (Kaschick; Kasik) was born August 18, 1840 in Kolin, Bohemia, a mountainous and rocky land. Mary Hula, daughter of Vaclav Hula and Katherine Sodorna Hula, was born August 18, 1844, near Kolin. George and Mary were married in 1862 in Bohemia. George was 22, while Mary was 18, and their lives were laid out before them like a clean, white canvas.

For twelve years, George and Mary lived in the beautiful, rocky, and mountainous country of Bohemia. Their first child, Elizabeth, was born January 16, 1865, followed by Wesley (Wenzl) born in 1868, then Mary in 1872 and Anna in 1873. As George worked as a stonemason and grew his family, word of America's Homestead Act began to spread throughout his community. Dreams of freedom and of land grew large in his mind and began to burn deep in his heart.

Mary's parents shared those dreams. When they, her brothers and sisters set sail for America in 1870, George and Mary grew restless to follow. The trip would cost more money than what they had, but they were determined. The next few years were spent trying to earn enough money for the voyage. Odd jobs were worked, and fire wood was cut to sell. By March of 1874, they were desperate to leave. Another boat to America was to set sail that month, so they took their firewood door to door to sell, but the winter season was now behind them and spring was on its way. No one wanted firewood.

Just when it seemed all hope was lost, they found a buyer for their firewood, a single person interested in purchasing an even larger quantity than what they had ready and available. With time running out and a shortfall of funds, George and Mary agreed to sell their entire lot of wood. But to make the pile larger and to sell a greater quantity than they actually had, they filled the center of their wood pile with straw. Before the buyer could move the pile and realize he purchased straw rather than wood, George and Mary, with four kids in toe, were on the high seas heading to America. But the journey would be more difficult than imagined.

The family of six departed from Breman, Germany via South Hampton, England, on the ship Brqunschweig in March of 1874. Wesley was six years old. There were 802 passengers on board and conditions were unspeakable. While aboard the ship, baby Anna became very ill. Passengers were told that if anyone should pass away while on the journey, the burial would be in the sea, and as Anna became weaker, Mary grew fearful of that fate for her precious baby. Mary and George agreed that should baby Anna die during the trip, they would lovingly hide her body and give her a proper burial in America once they arrived.

Their worse fears came true that fateful journey, and Anna's illness overtook her small and frail body. As planned, George and Mary hid the shell that once contained their precious Anna so that she would not be thrown overboard. But the journey drug on, and with each passing day, the decaying body made the sharks and whales fussed around the ship with hungry fury. The captain had made the journey enough to know what had happened. He called his crew and ordered them to make a search for a deceased body. Tragically, the crew found baby Anna and forced a burial at sea, the first of many tragedies that would shape George and Mary's life to come.

The ship finally arrived in Baltimore, Maryland two months later in May of 1874. The family, now only five of them. remained in Baltimore one year, picking cranberries and working odd jobs. After reconnecting with Mary's parents, they all headed west for Irving, Kansas. Mary was pregnant again with Joseph at this time, but made the long journey, giving birth to baby Joseph shortly after arriving in Kansas.

Along the Riley County Line, the Hulas and Kassiks found the small town of Irving, south of the Big Blue River, in a very fertile valley. Irving was a town in Marshall County, Kansas, located six miles southeast of Blue Rapids, along the Big Blue River. The Big Blue River was a stream that flowed through Johnson and Jackson counties. Many Czechs, coming from rocky, hilly land, were drawn to this areas south of Blue Rapids; and George, coming from the rocky, mountainous country in Bohemia, said "If land could grow rocks, it must be good land". It was 1875 now, and though many settlers in the area were becoming discouraged due to harsh conditions, it was here they settled. George and Mary settled on a quarter of land four miles southwest of Irving, the northeast quarter of section 34. The Hula's filled claim about 1/2 mile south over the valley.

The Kassik family lived on open land and possibly in their covered wagon until George was able to dig a dwelling out of a hill next to a creek and under the shelter of several large trees. This dugout was approximately 8 foot by 10 foot and became the start of what George, Mary, and their children called home in the new land.

Having worked with stone and mason prior to coming to America, George leaned on his skills and was able to line this new shelter with stone carved out of the hill on his property. He was intent on giving his family more than a dirt floor on which to lay their heads at night. Though it was only a dugout, it was home with beautiful stone walls and floors.

The Kassiks and Hulas were welcome to the area by a dry, hot summer, nearly intolerable. Locals were still talking about the drought of '74 and the unrelenting western winds, but it wasn't long when those same winds changed and shifted to the north. Relief was thought to be in sight, but instead came the migration of the grasshoppers. The insects presented a home in the atmosphere, filling the sky like a heavy fog, and blocking the sun from its energy and light. The insects were ravenous, and every living plant, tree, weed or crop became their victim. Once the vegetation in the areas was devoured, the grasshoppers moved onto boards and picket fences. Even the handles of hoes and rakes were destroyed. F.W. Giles, author of From Thirty Years in Topeka, wrote this of the invasion:

"It would tax the powers of a more abler writer than this to clearly portray the changes that ensued. The tree yesterday laden with its heavy drapery of green, today denuded. The peach and pear and apple trees, with luscious fruitage, withered as the fig tree accursed. Gardens with lawns and shrubbery and flowers, now lifeless, seared and fallen to decay. The cottage embowered, now exposed and blistered by the burning heat of the summer sun. The farmer's field of ripening grain -- his only promise, his only hope -- now blackened by the countless myriads of the all-devouring plague, Egypt's dread. A summer scene, in an hour, as it were, transformed to one of winter. To see it, only is it possible to realize it. There was alarm throughout the state, but especially in those districts of the west but recently settled, and the inquiry went out from every quarter, 'What shall be done?'"

Every known remedy to destroy the insects was used, but to no avail. As quickly as they came in and took everything nature and man had to give them, they moved out, traveling to the next sight for their destruction. A Nebraskan estimated the swarm to be 1800 miles long and 110 miles wide. How the Kassik family survived these days, living in a hole in the hill, trying ot make a life, build a house, and farm the land, is beyond imaginable.

The next test of endurance for the 300 residents of Irving and our Kassik family came on May 30, 1879. The day started out as any other for George, Mary, and their six children, but by dark, heavy clouds began to form from the southwest and northwest. Their appearance was considered nothing unusual except that they came up very suddenly, yet still quietly. In a short time, these innocent clouds were thrown into the most terrible commotion as our history book began to write yet again. Irving was hit by two cyclones that afternoon, an hour apart.

The northern half of the promising town was hit first with complete devastation. Before George and his family could emerge from their dugout, before the shocked and stunned residents could begin to emerge from the cellars and take in what had happened, a second tornado hit the southern half of the town. It was estimated at nearly two miles wide, with the Kassik's and Hula's new homes in its path. In the total darkness that prevailed during the raging storm, more than 34 homes and businesses were lost, as were 17 to 40 lives. Some people were supposedly never found. This tornado, more than any, gave Kansas the nickname, "The Cyclone State," yet the Kassik and Hula families survived.

In the midst of natural disasters and ongoing, unrelenting destruction of the area; and in the midst of building a home, plowing fields and growing crops, George and Mary sought education for their kids. Not able to read or write themselves, and very much loners in the community, these parents woke their kids each morning, dressed them, and sent them off to a Czech school in the Irving area. Elizabeth, Wesley and Mary were never taught to speak English. Only the siblings born after arriving in America (Joseph, George Jr., Emma, Johnny, and Frank) became fluent in the local tongue, able to communicate fluently with those around them.

Five years passed, and George and his family were doing all they could to endure yet another drought which lasted most of all 1879 through 1880. The summers of hot, dry weather brought on crop failures, and people became disheartened. George seemed to have put his worries, fears, time and energy into doing all he could with his home in the hill. With the family continuing to grow, George worked tirelessly to add space, expanding his dwelling one room at a time.

The dirt and stone dugout they first called home was transformed to the root seller and was used to store dried meats, eggs, milk and home canning. Walls two feet thick and made of the native rock from inside the earth around them helped form the first addition, a little kitchen about 8 foot by 12 foot.

The next addition was a 10 X 12 bedroom. By now, six years had passed since arriving in America, and twelve-year-old son, Wesley, helped build and carve the narrow and crooked stairway that let to two small bedrooms above the other areas. The first room upstairs had a door opening out on the top of the cellar, which opens off the kitchen below. One door and small holes for windows finally made the house complete. It was now around 1880, George and Mary's family had expanded to include the ten of them - Elizabeth, who was now 15, Wesley age 12, eight year old Mary, five year old Joe, George at age 4, Emma age 3, Johnny age 1, and baby Frank born in 1881, all playing out their lives in the two-room dwelling built single-handedly by their father.

Hard, tireless work was the life of George and Mary Kassik. Fields were plowed and soil was worked to provide food for their hungry mouths and bellies. Stones were unearthed from fields to make way for better crops beautiful stones unusually smooth and large in size (often two feet thick and three feet long, with many being nearly a foot tall). George resourcefully used what nature had provided and cemented them into place, erecting a barn and stalls. Before long, a smaller barn, a small shed closer to the house, and a chicken house was also added, making his homestead dream complete.

Mary had her own source of strength. Uncommon in those days, Mary would have a baby, stay in bed one day, and then be found up and about the next, tending to the day's chores, inside or out. Being in bed was not an option for the Kassiks. There was too much work to be done. They were workers and survivors.

What portion of the land he could not use for himself, George rented to Lucas Frasher. His tenacity, hard work, and discipline insured that his land was always free of mortgage. All this, along with his love for land, he passed on to his children.

The lives of those ten dreamers took place for the next few decades. They celebrated birthdays and weddings, and mourned the loss of loved ones along the way. When the Oklahoma land run occurred in 1893, son Wesley, now 25, was the only boy in the family old enough to participate in the exciting race. Still unable to speak the local language, he traveled on a small brown pony with some friends to re-live the homesteading dream of his father. Somehow, Wesley was separated from his companions and was on his own. The friends were never able to secure any land, but Wesley, like his father, was a determined fighter and survivor. He secured his land, which was 16 miles southeast of Alva, near Dacoma; completed the require, lawful arrangements in Alva; then made the 300-mile journey back home. All were indeed surprised to learn he had fared so well. He would arrange to buy farms for $300 or a team of mules for his brothers, George and Frank.

More years passed and the history book pages continued to turn. Irving, Kansas and the home of the beloved Kassiks fell under attack of Mother Nature yet again near the turn of the century. Rainfall was above normal during the first half of May 1903 in northeast and north-central Kansas. As a result, the soil in that area was already saturated when excessive rains began again in late May. The lack of surface storage in the river basins and already saturated soils led to the events on June 4, 1903, when the Big Blue River went on a rampage. Thirty-two- to thirty-four-feet above normal, the swollen stream carried homes, crops, livestock and bridges down the valley.

Mary Hula Kassik's parents had settled in the valley and were living in Irving at the time of the tragic flood. As the waters rose in and around their home, they brought their livestock into the house, leading them upstairs to higher ground. Finally, Mary's parents decided to hang a red flag from their home to signal their distress. A neighbor finally saw the signal. With the help of his sons, the neighbor made a raft to rescue the family.

Another tragedy stuck in 1905, when a fire broke out in a local store, burning it to the ground, and again, in 1907, where 4 more businesses burned. That following year, in 1908, the Big Blue River threatened to destroy the area again. The townspeople were prepared, however, and were able to keep the river within its banks.

George continued to be successful in business affairs, stone masonry, and farming. He died on December 20, 1909, following an illness of three weeks. He is buried in the Czech Moravian Cemetery in Blue Rapids, Kansas. His funeral was held at his home south of Irving.

George never lived to see the rise and fall of Irving, Kansas, in the next few years. In 1910 the population was estimated at 403 and was beginning to establish good banking facilities, a weekly newspaper, telegraph and express offices, a grade school, public library, churches of all denominations, and three rural routes began to run from the Irving post office. But tragedy continued, and in 1916, fire struck yet again, burning most of the north side of Main Street. Irving was the home to a survivor mentality, however, and they rebuilt after each tragedy.

Mary Hula Kassik died on March 7, 1922 at 77 years of age after an illness of 10 days in the stone dwelling where she and her husband lived their lives in America. At her time of death, Irving had grown to be the town of their hopes and dreams.

But Mother Nature's rage on Irving and the people, our ancestors, living there continued. With excessive rains and flooding again in 1941 and 1951, the Corp of Engineers finally stepped in and announced plans for the construction of the Tuttle Creek Dam. The population started to decrease and many businesses closed, including the post office. The Corp of Engineers eventually bought out any remaining homes, and any business that was able to survive moved to Blue Rapids. The town-site was abandoned in 1960.

The town's road network is visible to this day, foundations for buildings and homes can still be seen, and a stone monument marking the town of Irving from 1859-1960 sits in a makeshift park, along with a mailbox and notebook in which visitors can write notes.

George and Mary's son, John (Johnny), resided in the family home until he passed away in 1963. He was 83 years of age. No running water, electricity, or bathroom existed in the home, but the thick stone walls carved out of the American soil by the hands of a Bohemian dreamer kept the dwelling cool in the hot summer sun and warm in the dark days of winter. Though abandoned, the 135 year old home still stands, and will stand for another 100 years. Hidden in a little gully not seen from the road, its chimney is strong, and the roof is in place.

The chicken house may be crumbling, the barns falling down in ruins, the fences may no loner have purpose, but the land still holds stories of those who once called it home. Prairie grass ripples up to your waist, and the creek is now a dry bed of earth, but the trees still blow in the breeze. As you stand on the hill next to the broken windmill and look down into the dugout and into the house, you can hear the roar of a bond fire and see a glimpse of dancing shadows around it. The aroma of something delicious takes your breath away, but just for a moment, then gone. A fiddle and an accordion play a Polka, as children's voices in an unfamiliar language ring out. Yes, the music, the dancing, and the fragrance of fresh-baked kolaches were the foundation and the thread running through our ancestors that kept them going. And these are the things that still remain in all of us. This family, the chickens, horses, and cattle have all returned to the earth, to the land that sustained them for their time. And the land still goes on and is plentiful.

As Bob and I continued to sit there and look onto the land once belonging to our ancestors, there in the needles and under the growth of the stream's edge, we imagined (and saw in our minds) a huge fire, red and golden. Leaping up to the light were the weird shapes of the old trees and stone barns and corrals. Silhouetted against the flames was an old farmer, bent from years of building homes, from stone and toiling the sod in the earth. His fiddle was tucked under his chin and from it came the most exciting music I could imagine every hearing. While we heard fiddles play before, they had played western swing, nothing like we were hearing now. This music was different. It was wailing and melancholy, and it made me want to reach out my arms and scream, and then it would change, and there would be such a wild and strong beat that I felt I must get up and dance.

As we talked about this and watched and listened with our imaginations, we could almost see a figure stand up on the other side of the fire. This was a small boy of 10 or 12 with ragged pants, no shirt, bare feet. He was playing an accordion practically as big as himself. His fingers flew over the keys as he danced and sang around the fire. At the same time a girl about 15, her hair flowing to her waist, dark as night, stood. She raised her hands over her head and began to clap them in time to the music. We began to tap our feet. The music got faster and faster, and four little kids rose. All bare foot and dirty, ages 8 to 1. Screaming, clapping and dancing, the girl began to whirl and twirl around the fire. Ragged skirts flying out, just missing the flames. The she flopped down flat on her back, stretching her arms and legs out in pleasure. Nearby sat her mother, holding her baby on her swollen stomach. She was dark, like the Czechs, hair pulled back at the nape of her neck, sleek and black. She looked faded and worn. She was just sitting there with her head leaning against a tree. Her face was gray, and little beads of sweat stood out on her forehead. She tried to push strands of hair back from her face, which was alive with the reflection of the fire. Her voice started to ring out. It was gentle but stood out from everyone. She sang of the old country, the tunes were an enchanting melody, all of their own. The fiddle wailed again. The small children, ragged and dirty, like tinkers children, fell to the ground in a heap, exhausted, and fell asleep immediately. Mary slowly rose, spirits high, holding her sleeping baby on one hip, covered the sleeping children with a blanket from her shoulders, and entered the small stone house, her home.

For the first time I was aware that somewhere in the world there was more than just growing up and having children and being respectable. There were huge things and terrible unidentified longings, dreams that had no visible shapes but that you still had to reach up for. I felt I would never be satisfied with anything in my life every again. We stood there for hours, Bob and I, or so it seemed, until the fiddle was put down and the fire turned into a flicker. Then we saw him and the boy roll themselves into blankets, and the girl on the other side doing the same. We realize it was more than just a vision. We had a foretaste of that heavy potion called life.

(Naomi Lucille Kassik White, Judith Suzaanne White Kinndard, and Susan Rochelle Kinnard Gates)

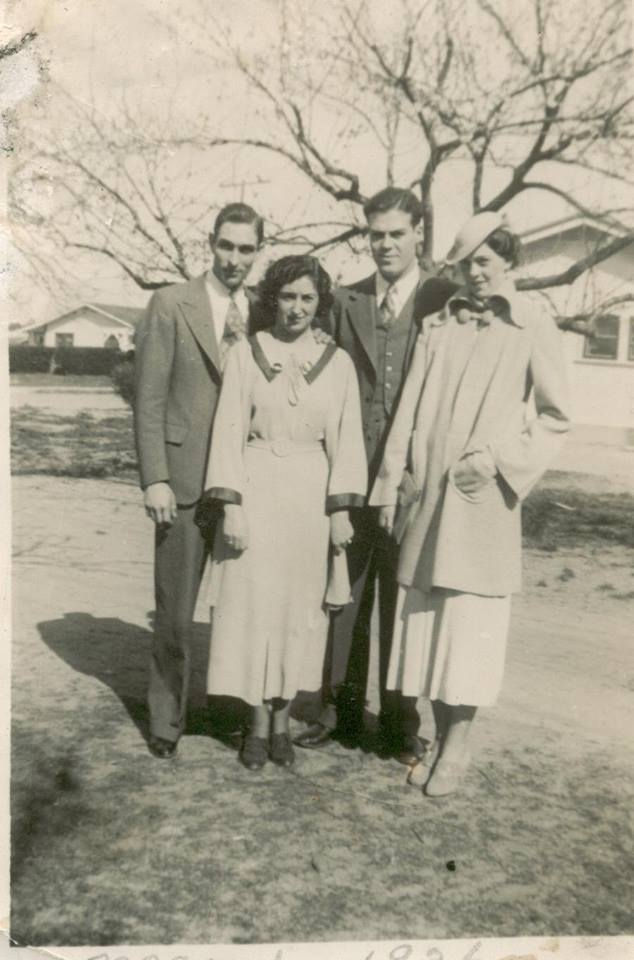

March 1936 in Dacoma

Bertha Hiatt Sweeney on far left

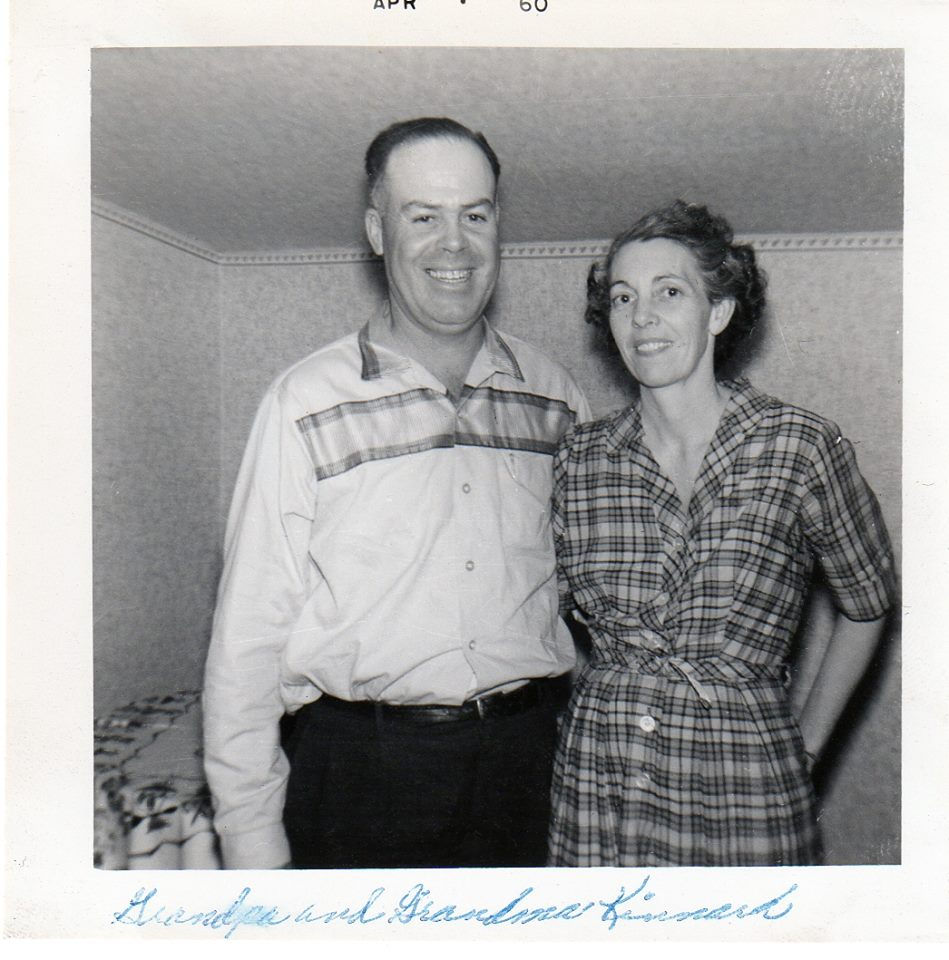

Eldora Faye and James (Jim) Kinnard. Parents of Robert James Kinnard, my dad.

Grandpa and Grandma Kinnard on the Right

Faye and Jim Kinnard 1935

Comments